It’s been a rough two weeks. Alton Sterling was killed by a police officer in Baton Rouge, LA while hustling CDs outside a food mart. Philando Castile was killed by a police officer near St. Paul, MN during a traffic stop. Mass Action Against Police Brutality organized a speak out and march in Roxbury, where hundreds of people came out to show their respects. This was a sad, but moving event. When someone breaks down in front of a crowd, talking about how their brother or son was killed by police, you can’t help but grieve with them. And that’s what we did — we grieved with and tried to support one another.

The day after the Roxbury rally, a friend told me she was shaken up by the shootings. She’s an artist, she’s a woman of color, and her car has a broken taillight. “I could be executed for that, just … just like that guy in Minnesota”. It’s hard to hear someone say that, but that is what people of color deal with in the United States. Inequities like these need to be acknowledged.

Of course, there were also five police officers killed by a sniper in Dallas, TX, and three more police shootings in Baton Rouge over the weekend. These too, were tragic events.

Every police officer death is followed by numerous reminders of the risks they face. I’ll acknowledge that policing can be a difficult job, but I also believe the levels of danger are overstated.

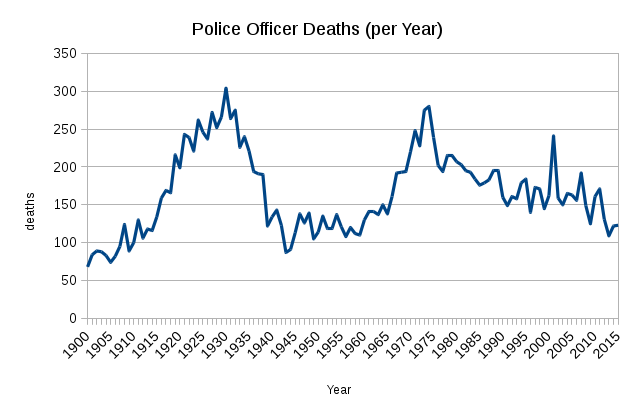

The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund publishes a list of officer deaths by year, from 1791 to present. Here’s what NLEOMF’s data looks like, during the years 1900–2015:

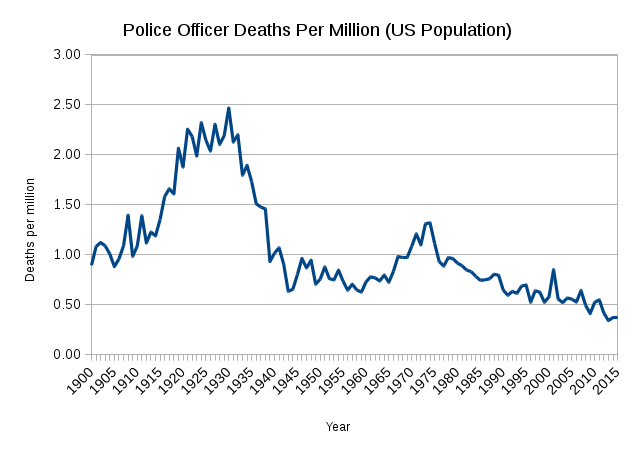

Two things jump out from this statistics: the number of police deaths per year has been declining since the mid 1970s (albeit for a spike in 2001 — the year of the world trade center attacks). But this doesn’t tell the whole story. The population of the United states has changed since 1900, and what we’re really interested in is the rate of police deaths, relative to the rest of the population. Here’s another graph, where I’ve incorporated US Census data and calculated police deaths per million population.

If you’re willing to accept officer deaths per year as a proxy for “safety”, then it’s pretty obvious that being a police officer has gotten safer over the last four decades. Officer death rates today are nothing like we saw during the 1920’s and 1930’s.

So what went on during the 1920’s and 1930’s? About a year ago, the American Enterprise Institute published a similar set of graphs, but they focused on firearm-related police deaths (as opposed to all police deaths). AEI derived their charts from a different data set, but the general curve is similar to what you see above. Especially the piece that shows officer deaths in general decline since the mid 1970’s. AEI also draws a correlation (though not a causal relationship) between prohibition and the high officer death rates of the 1920s and 1930.

Prohibition was our first war on drugs, and it didn’t work out the way its supporters had hoped. In particular, criminalizing the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcohol turned bootlegging into a highly-profitable criminal enterprise. Prohibition changed the way people drank, but it didn’t stop them from drinking.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that policing is dangerous, and that we should do something to reduce the risks that officers face. I have a few suggestions: We don’t need police officers risking their lives to give a ticket for a broken tail light. We don’t need polices officers risking their lives to rough someone up for selling cigarettes on the sidewalk. We don’t need police officers risking their lives to shake down kids who might be carrying a couple of joints. We don’t need the laws that force police officers to risk their lives, by putting them in direct conflict with the communities they patrol.

And we especially don’t need members of our communities risking their lives, every time they have an encounter with the police.

It’s been a rough two weeks. Alton Sterling was killed by a police officer in Baton Rouge, LA while hustling CDs outside a food mart. Philando Castile was killed by a police officer near St. Paul, MN during a traffic stop. Mass Action Against Police Brutality organized a speak out and march in Roxbury, where hundreds of people came out to show their respects. This was a sad, but moving event. When someone breaks down in front of a crowd, talking about how their brother or son was killed by police, you can’t help but grieve with them. And that’s what we did — we grieved with and tried to support one another.

The day after the Roxbury rally, a friend told me she was shaken up by the shootings. She’s an artist, she’s a woman of color, and her car has a broken taillight. “I could be executed for that, just … just like that guy in Minnesota”. It’s hard to hear someone say that, but that is what people of color deal with in the United States. Inequities like these need to be acknowledged.

Of course, there were also five police officers killed by a sniper in Dallas, TX, and three more police shootings in Baton Rouge over the weekend. These too, were tragic events.

Every police officer death is followed by numerous reminders of the risks they face. I’ll acknowledge that policing can be a difficult job, but I also believe the levels of danger are overstated.

The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund publishes a list of officer deaths by year, from 1791 to present. Here’s what NLEOMF’s data looks like, during the years 1900–2015:

Two things jump out from this statistics: the number of police deaths per year has been declining since the mid 1970s (albeit for a spike in 2001 — the year of the world trade center attacks). But this doesn’t tell the whole story. The population of the United states has changed since 1900, and what we’re really interested in is the rate of police deaths, relative to the rest of the population. Here’s another graph, where I’ve incorporated US Census data and calculated police deaths per million population.

If you’re willing to accept officer deaths per year as a proxy for “safety”, then it’s pretty obvious that being a police officer has gotten safer over the last four decades. Officer death rates today are nothing like we saw during the 1920’s and 1930’s.

So what went on during the 1920’s and 1930’s? About a year ago, the American Enterprise Institute published a similar set of graphs, but they focused on firearm-related police deaths (as opposed to all police deaths). AEI derived their charts from a different data set, but the general curve is similar to what you see above. Especially the piece that shows officer deaths in general decline since the mid 1970’s. AEI also draws a correlation (though not a causal relationship) between prohibition and the high officer death rates of the 1920s and 1930.

Prohibition was our first war on drugs, and it didn’t work out the way its supporters had hoped. In particular, criminalizing the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcohol turned bootlegging into a highly-profitable criminal enterprise. Prohibition changed the way people drank, but it didn’t stop them from drinking.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that policing is dangerous, and that we should do something to reduce the risks that officers face. I have a few suggestions: We don’t need police officers risking their lives to give a ticket for a broken tail light. We don’t need polices officers risking their lives to rough someone up for selling cigarettes on the sidewalk. We don’t need police officers risking their lives to shake down kids who might be carrying a couple of joints. We don’t need the laws that force police officers to risk their lives, by putting them in direct conflict with the communities they patrol.

And we especially don’t need members of our communities risking their lives, every time they have an encounter with the police.