On Friday November 13th a group of armed fellows shot up, and attempted to blow up parts of Paris. In the process, they killed approximately 130 people. That’s tragic. I’m sad that it happened, and I feel really bad for the people affected.

But then again, I’m from the United States — where mass shootings are quickly becoming a routine thing. Our mass shootings generally involve a smaller number of fatalities, but we definitely make up for it in volume.

Shootingtracker.com tracks mass shootings in the US, which they define as “when four or more people are shot in an event, or related series of events, likely without a cooling off period.” Their data covers 2013–2015 in detail, but we can summarize it like this

| Year |

# mass shootings |

# killed |

# wounded |

| 2013 |

363 |

502 |

1,266 |

| 2014 |

336 |

383 |

1,239 |

| 2015 (through 11/8/2015) |

325 |

406 |

1,196 |

Bear in mind that these are only mass shootings — four people or more. We’re not talking about homicide in general.

We can look at other kinds of killings. According to the Guardian’s The Counted project, 1019 people were killed by police (so far) in 2015, 900 of these by gunshot. We can also look at significantly greater death tolls due to done strikes, or US military campaigns in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Why am I lumping all of these things together? There are many different ways to categorize violence, but I tend to gravitate to the spectrum of “worse”. Along this spectrum, we can say that the type of violence A is worse than type of violence B if A produces more causalities than B. Put another way, the more people get killed, the worse it is.

Let’s show some relationships along this scale. I’ll use “>” to mean “worse than”.

civilian deaths due to military campaigns > police killings > mass shootings > terrorist attacks

In plain English, military campaigns are worse than police killings; police killings are worse than mass shootings; and mass shootings are worse than terrorist attacks. And yet, we focus on terrorism, which lies at the bottom end of the scale. I have a couple of theories as to why this might be:

- Terrorism is scary. It plays upon people’s instincts of fear, and a fearful population is easier to control.

- Government agencies want to play up the idea of “we’re doing everything we can to prevent terrorism”. In short, the war on terror is fertile ground for security theater.

- There’s a group of people who find the war on terror highly profitable. It’s a racket, and somebody’s making a lot of money.

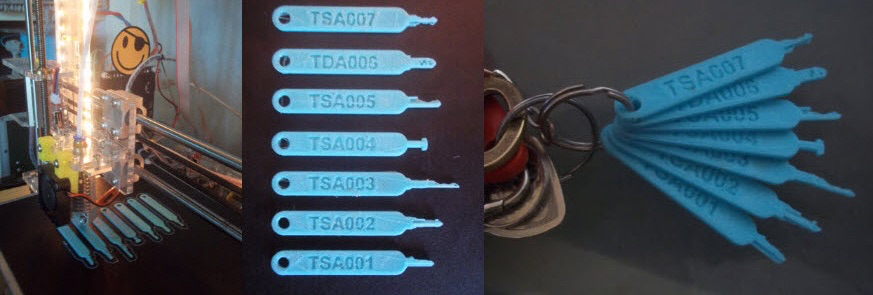

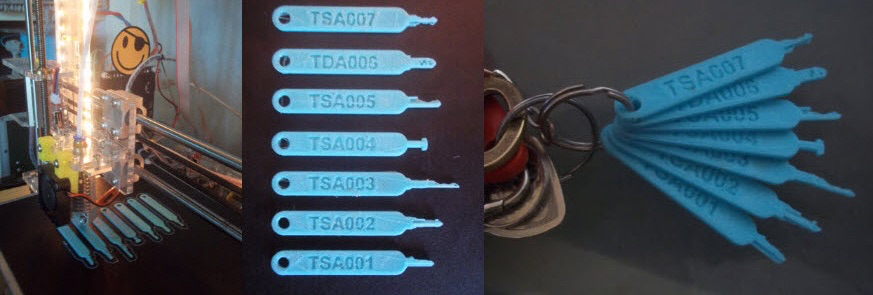

The TSA is a good illustration of all three points. Airplane hijackings are scary, but extremely rare. The TSA spent $160M on a body scanner program. During an audit, TSA agents failed to detect explosives and weapons in 67 out of 70 tests. Lots of money spent; very little to show for it.

Post Paris, there’s been the usual hype about encryption and the internet: encryption prevents the government from reading people’s communications, and therefore encryption helps terrorists; the internet allows people to spread ideas, some of these ideas involve terrorism, and therefore, the internet helps terrorists. At this point, we don’t know whether the Paris attackers used encryption, but we have some evidence that they did not.

It’s hard to reconstruct acts of violence after the fact, let alone predict them in advance. But we do know the Paris attackers used bombs and automatic weapons. So far, no one has called for a ban on small arms or gunpowder, and no one is asking for gun manufacturers to modify their products, so that they’re less useful to terrorists, or less harmful to members of law enforcement. Guns and light ordinance are okay, but the internet — that shit’s dangerous!

In short, the “war on terrorism” is nothing more than a war on our ability to communicate, and our ability to share ideas. At this point, it’s worth pointing out one of the recommendations of the 9/11 commission.

Recommendation: The U.S. government must define what the message is, what it stands for. We should offer an example of moral leadership in the world, committed to treat people humanely, abide by the rule of law, and be generous and caring to our neighbors. America and Muslim friends can agree on respect for human dignity and opportunity. To Muslim parents, terrorists like Bin Ladin have nothing to offer their children but visions of violence and death. America and its friends have a crucial advantage-we can offer these parents a vision that might give their children a better future. If we heed the views of thoughtful leaders in the Arab and Muslim world, a moderate consensus can be found.

That bit about offering “an example of moral leadership to the world” — we really said that. I suspect our message and vision of a better future weren’t very good. As bad as ISIS is, there are many people who find their propaganda far more appealing than ours, and that’s a shortcoming we really have to think about. The war on terror is not a war against nations; it is a war against people. If you want to win that kind of war, the first step is getting the people on your side.

On Friday November 13th a group of armed fellows shot up, and attempted to blow up parts of Paris. In the process, they killed approximately 130 people. That’s tragic. I’m sad that it happened, and I feel really bad for the people affected.

But then again, I’m from the United States — where mass shootings are quickly becoming a routine thing. Our mass shootings generally involve a smaller number of fatalities, but we definitely make up for it in volume.

Shootingtracker.com tracks mass shootings in the US, which they define as “when four or more people are shot in an event, or related series of events, likely without a cooling off period.” Their data covers 2013–2015 in detail, but we can summarize it like this

Bear in mind that these are only mass shootings — four people or more. We’re not talking about homicide in general.

We can look at other kinds of killings. According to the Guardian’s The Counted project, 1019 people were killed by police (so far) in 2015, 900 of these by gunshot. We can also look at significantly greater death tolls due to done strikes, or US military campaigns in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Why am I lumping all of these things together? There are many different ways to categorize violence, but I tend to gravitate to the spectrum of “worse”. Along this spectrum, we can say that the type of violence A is worse than type of violence B if A produces more causalities than B. Put another way, the more people get killed, the worse it is.

Let’s show some relationships along this scale. I’ll use “>” to mean “worse than”.

In plain English, military campaigns are worse than police killings; police killings are worse than mass shootings; and mass shootings are worse than terrorist attacks. And yet, we focus on terrorism, which lies at the bottom end of the scale. I have a couple of theories as to why this might be:

The TSA is a good illustration of all three points. Airplane hijackings are scary, but extremely rare. The TSA spent $160M on a body scanner program. During an audit, TSA agents failed to detect explosives and weapons in 67 out of 70 tests. Lots of money spent; very little to show for it.

Post Paris, there’s been the usual hype about encryption and the internet: encryption prevents the government from reading people’s communications, and therefore encryption helps terrorists; the internet allows people to spread ideas, some of these ideas involve terrorism, and therefore, the internet helps terrorists. At this point, we don’t know whether the Paris attackers used encryption, but we have some evidence that they did not.

It’s hard to reconstruct acts of violence after the fact, let alone predict them in advance. But we do know the Paris attackers used bombs and automatic weapons. So far, no one has called for a ban on small arms or gunpowder, and no one is asking for gun manufacturers to modify their products, so that they’re less useful to terrorists, or less harmful to members of law enforcement. Guns and light ordinance are okay, but the internet — that shit’s dangerous!

In short, the “war on terrorism” is nothing more than a war on our ability to communicate, and our ability to share ideas. At this point, it’s worth pointing out one of the recommendations of the 9/11 commission.

That bit about offering “an example of moral leadership to the world” — we really said that. I suspect our message and vision of a better future weren’t very good. As bad as ISIS is, there are many people who find their propaganda far more appealing than ours, and that’s a shortcoming we really have to think about. The war on terror is not a war against nations; it is a war against people. If you want to win that kind of war, the first step is getting the people on your side.